04.05 / 09.06 2019. FASTIR PUNKTAR

Artists / Listamenn:

Helene Garberg

Kah Bee Chow

Bjarni Þór Pétursson

Þorbjörg Jónsdóttir

Curators / Sýningarstjórar: Bjarni Þór Pétursson, Gústav Geir Bollason

Text/Texti: Shauna Laurel Jones (see below)

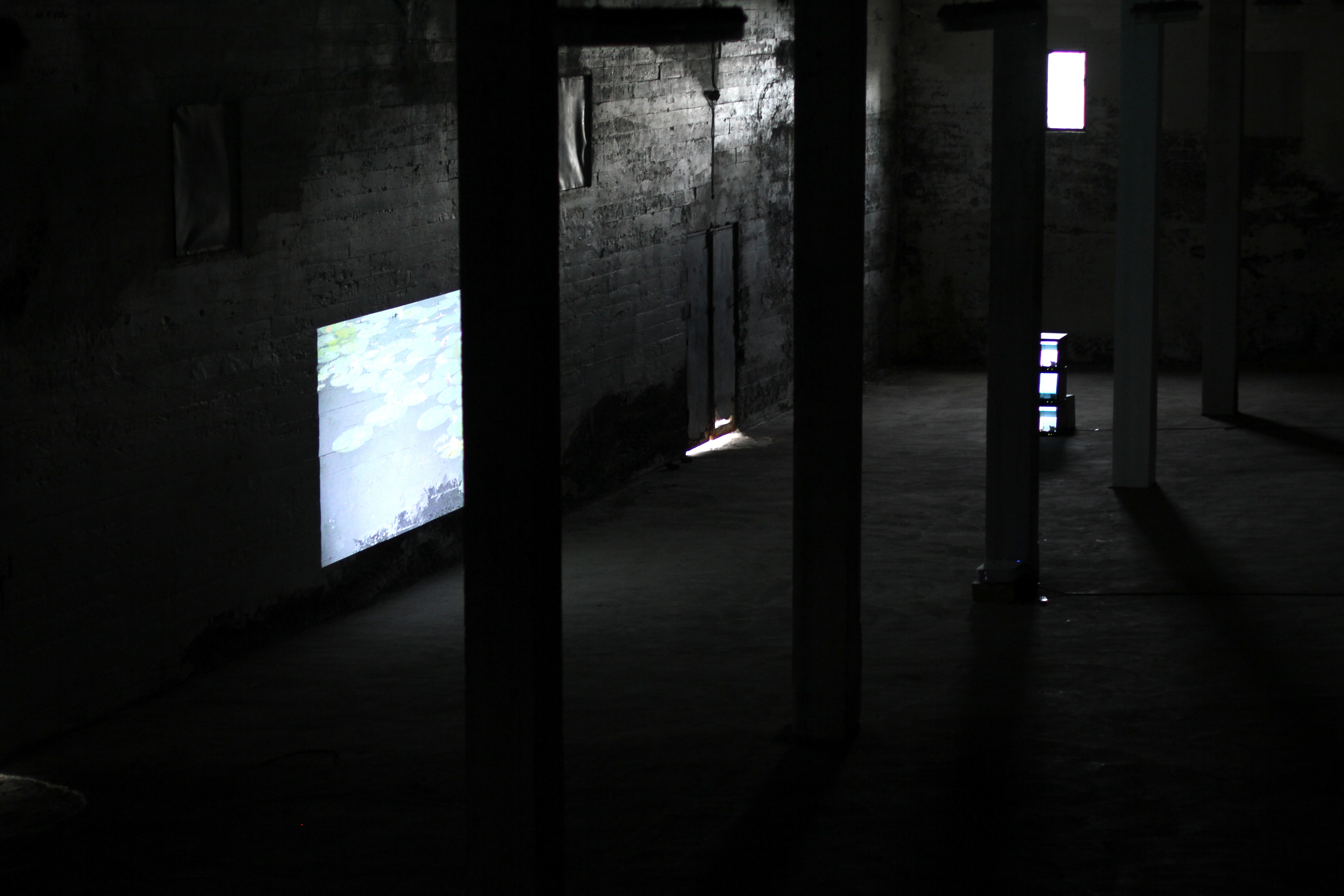

Far away and yet closer than ever, four artists sought to weave a translucent veil separating our world from another. Together, the film and video imagery by Bjarni Þór Pétursson, Helene Garberg, Kah Bee Chow, and Þorbjörg Jónsdóttir suggests a place in which matter is secondary to myth, where transformation and rematerialization happen regularly as a matter of course.

Fixed Points sýnir hreyfimyndir sem sökkva sér í goðafræði og draumaveröld náttúrulegra svæða. Myndað er á mörgum stöðum svo sem eins og Yucatán í Mexíkó og Amasón héraðið í Kólumbíu, þar sem listamennirnir skoða og rannsaka sérkenni, sögu og andrúmsloft viðfangsefnis og staða.

“Beyond seven mountains, beyond seven forests…” Thus begins a typical fairytale in Poland. In Korea, the tone is set with “Once, in the old days, when tigers smoked…”i And in the far north of Iceland, here in Hjalteyri, the tale might start with the invocation, “Far away and yet closer than ever, when you open your eyes by closing them tight…”

The Four Artists and the Veil

Far away and yet closer than ever, four artists sought to weave, collectively, a translucent veil separating one realm from another. On one side of this thin gauze was our world as we live it, and on the other side, the world they knew: a place in which matter is secondary to myth, where transformation and rematerialization happen regularly as a matter of course.

It was a place where Don William—the indigenous shaman Þorbjörg Jónsdóttir met in the Colombian Amazon—might have explained why “a man is like a tree,” but he could equally have said, “A man is a tree.” For a person can become a tree, in the four artists’ world, simply by feeling the sap coursing through her veins and allowing her branches to stretch ever so slowly heavenwards.

It was also a place where Nature had strong feelings, too, about her form. The land’s idea of its own shape was important, so important it could overpower the other ideas and (market) forces trying to reshape it. Seen from above, the contours of Malaysia’s Penang Island resemble a turtle, and the turtle is auspicious, Kah Bee Chow remembers a teacher once telling her. And so Kah Bee watched with skeptical interest as high-rise condominiums were erected on Penang, recontouring the auspicious coastline with buildings found later to be architecturally unsound. The luxury glass-ensconced buildings would remain uninhabited. Was it the spirit of the turtle, perhaps, who tilted the high-rise off the vertical, a punishment for retracing her shape? Still, “maybe it is a good thing,” writes Gaston Bachelard, “for us to keep a few dreams of a house that we shall live in later, always later, so much later, in fact, that we shall not have time to achieve it…It is better to live in a state of impermanence than in one of finality.”ii And so Kah Bee’s looped video kept that dream alive, the dream of the almost-done glass house.

Bachelard, the great phenomenologist who sought to understand the relational properties of space, would have felt at home in the four artists’ malleable world. Describing the symbiotic relationship between internal and external, he invokes the poet Rilke, who wrote of a profound experience in a forest: “These trees are magnificent, but even more magnificent is the sublime and moving space between them, as though with their growth it too increased.”iii Þorbjörg and her shaman in the Amazon felt that space, too. And when Þorbjörg searched for the otherworld through the landscape of the jungle, she did not search there because the jungle was foreign, other; she searched there in the same way she did in her native Iceland, interrogating where the rifts in the material land might give way to some greater essence. “Together,” says Þorgbjörg, “the dense jungle and the barren glacier desert form the same circle,” different options on the same continuum that is landscape. The moving space between Þorbjörg’s and Rilke’s trees is alive with potential, a means of translocation.

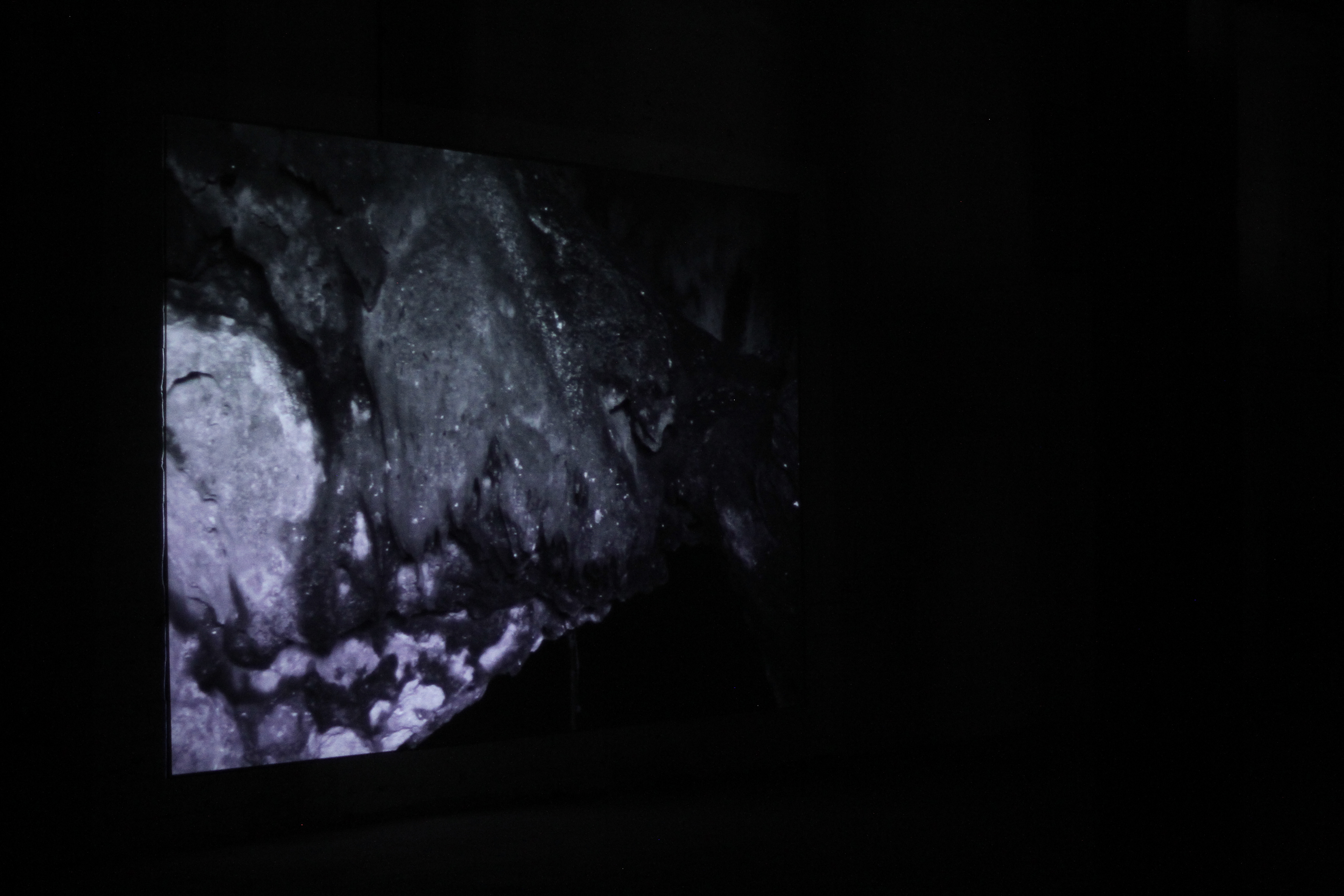

Those Amazonian trees are lush and green, while Helene Garberg’s trees in Mexico’s Yucatán start out so overexposed that they hardly register as such. And so it was that the artist Helene journeyed through a blizzard of lush and white to reach the entrance to the cenote—one of the underground caverns that was said to be the portal into the Mayan underworld—and allowed it to draw her in. The filmic poetry she conjured up out of that cenote sang of alchemy, of liquid rock, of the futility of trying to define one’s sense of scale in regard to the earth. Did Helene draw herself back out again? “If a landscape, as we say, ‘draws us in’ with its seductive beauty,” writes the art historian W. J. T. Mitchell on the nature of landscape in Western art, “this movement is inseparable from a retreat to a broader, safer perspective, an aestheticizing distance, a kind of resistance to whatever practical or moral claim the scene might make on us.”iv But no, Helene did not retreat; her aestheticizing was not an act of distancing; she did not withdraw, and those who would watch her poem would be hard pressed to resist the claims the cenote made on them.

And what of the fourth artist; what distant land did he travel to? The fourth artist, Bjarni Þór Pétursson, went to the farthest place of all: the Land of Real Vulnerability, the most demanding region to access because it is, in fact, far too close. His sets were sparse, his camera slow-panning, if it panned at all; what walked onto the stage, a human dressed as animal, could not have been read as absurd because it was so hard to read at all. It was as if something strange and familiar emerged from the Jungian abyss to claim a new archetype, that of the Watcher Watched, or perhaps the Seer Seen. And when, against all odds, Bjarni captured the abyss and brought it to the other side of the stage, where the audience was supposed to be, the plush theater seats vanished into thin air.

So it was that it turned out nothing was fixed in Fixed Points. The four artists would part and go their separate ways, but they would be remembered for their confidence in the face of the uncanny, their light touch on subjects sometimes belabored by others. If you should find yourself in Hjalteyri, you might still find remnants of the artists’ veil, for they wove its diaphanous fibers into the frame of the ether itself, ready to be peered through by the curious and the brave.

It was a place where Don William—the indigenous shaman Þorbjörg Jónsdóttir met in the Colombian Amazon—might have explained why “a man is like a tree,” but he could equally have said, “A man is a tree.” For a person can become a tree, in the four artists’ world, simply by feeling the sap coursing through her veins and allowing her branches to stretch ever so slowly heavenwards.

It was also a place where Nature had strong feelings, too, about her form. The land’s idea of its own shape was important, so important it could overpower the other ideas and (market) forces trying to reshape it. Seen from above, the contours of Malaysia’s Penang Island resemble a turtle, and the turtle is auspicious, Kah Bee Chow remembers a teacher once telling her. And so Kah Bee watched with skeptical interest as high-rise condominiums were erected on Penang, recontouring the auspicious coastline with buildings found later to be architecturally unsound. The luxury glass-ensconced buildings would remain uninhabited. Was it the spirit of the turtle, perhaps, who tilted the high-rise off the vertical, a punishment for retracing her shape? Still, “maybe it is a good thing,” writes Gaston Bachelard, “for us to keep a few dreams of a house that we shall live in later, always later, so much later, in fact, that we shall not have time to achieve it…It is better to live in a state of impermanence than in one of finality.”ii And so Kah Bee’s looped video kept that dream alive, the dream of the almost-done glass house.

Bachelard, the great phenomenologist who sought to understand the relational properties of space, would have felt at home in the four artists’ malleable world. Describing the symbiotic relationship between internal and external, he invokes the poet Rilke, who wrote of a profound experience in a forest: “These trees are magnificent, but even more magnificent is the sublime and moving space between them, as though with their growth it too increased.”iii Þorbjörg and her shaman in the Amazon felt that space, too. And when Þorbjörg searched for the otherworld through the landscape of the jungle, she did not search there because the jungle was foreign, other; she searched there in the same way she did in her native Iceland, interrogating where the rifts in the material land might give way to some greater essence. “Together,” says Þorgbjörg, “the dense jungle and the barren glacier desert form the same circle,” different options on the same continuum that is landscape. The moving space between Þorbjörg’s and Rilke’s trees is alive with potential, a means of translocation.

Those Amazonian trees are lush and green, while Helene Garberg’s trees in Mexico’s Yucatán start out so overexposed that they hardly register as such. And so it was that the artist Helene journeyed through a blizzard of lush and white to reach the entrance to the cenote—one of the underground caverns that was said to be the portal into the Mayan underworld—and allowed it to draw her in. The filmic poetry she conjured up out of that cenote sang of alchemy, of liquid rock, of the futility of trying to define one’s sense of scale in regard to the earth. Did Helene draw herself back out again? “If a landscape, as we say, ‘draws us in’ with its seductive beauty,” writes the art historian W. J. T. Mitchell on the nature of landscape in Western art, “this movement is inseparable from a retreat to a broader, safer perspective, an aestheticizing distance, a kind of resistance to whatever practical or moral claim the scene might make on us.”iv But no, Helene did not retreat; her aestheticizing was not an act of distancing; she did not withdraw, and those who would watch her poem would be hard pressed to resist the claims the cenote made on them.

And what of the fourth artist; what distant land did he travel to? The fourth artist, Bjarni Þór Pétursson, went to the farthest place of all: the Land of Real Vulnerability, the most demanding region to access because it is, in fact, far too close. His sets were sparse, his camera slow-panning, if it panned at all; what walked onto the stage, a human dressed as animal, could not have been read as absurd because it was so hard to read at all. It was as if something strange and familiar emerged from the Jungian abyss to claim a new archetype, that of the Watcher Watched, or perhaps the Seer Seen. And when, against all odds, Bjarni captured the abyss and brought it to the other side of the stage, where the audience was supposed to be, the plush theater seats vanished into thin air.

So it was that it turned out nothing was fixed in Fixed Points. The four artists would part and go their separate ways, but they would be remembered for their confidence in the face of the uncanny, their light touch on subjects sometimes belabored by others. If you should find yourself in Hjalteyri, you might still find remnants of the artists’ veil, for they wove its diaphanous fibers into the frame of the ether itself, ready to be peered through by the curious and the brave.

There, that is a story.

—Shauna Laurel Jones