20.05 / 16.07 2023

SIGURÐUR GUÐJÓNSSON > LEIÐNI LEIÐIR

( ÍSL. FYRIR NEÐAN )

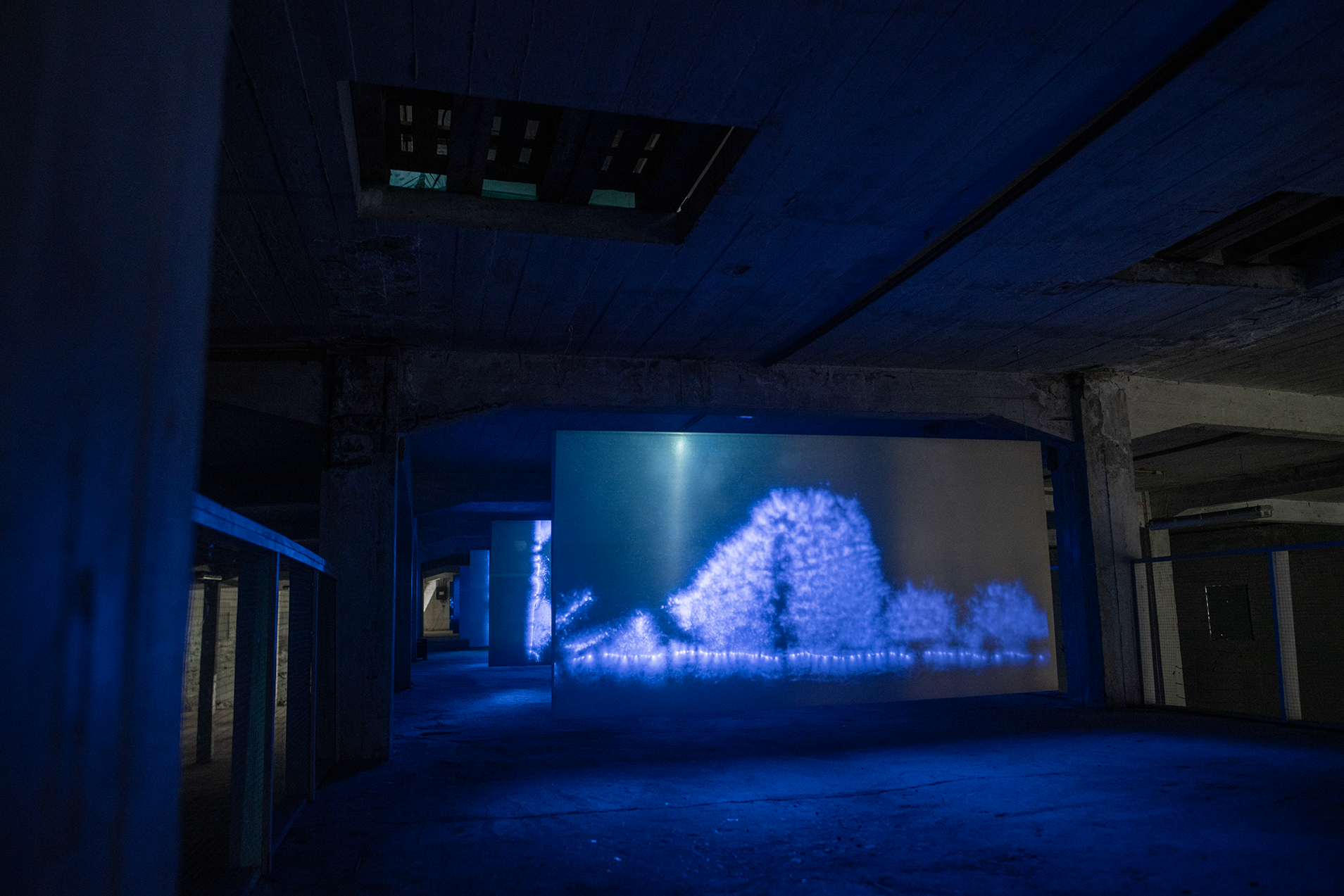

Through an extensive installation involving moving images and sound, Sigurður Guðjónsson has transformed the 2000-square-meters space of the former factory in Hjalteyri into a multisensory sculpture. Philosopher Jóhannes Dagsson met the artist to discuss the installation and explore how it plays with time and energy.

JD: Presumably, the installation involves a single soundscape?

SG: I have conceived of the building as a sonic environment: its wings are like separate audio channels, left and right, like a stereo system. On the mezzanine ceiling, there are holes that I use for the sound. The sound travels between these holes, so it will organically follow the viewer as they walk through the piece. Then on the ground floor, there is a tunnel where recordings of reverb are being played. The tunnel is forty metres long, so it takes time for the sounds there to seep into the rest of the building. There are several layers that make up the soundscape. First, I’m working with the electronic sounds from the video footage used in the installation, which I then manipulate as part of my process; I’m also working with recordings of resonance inside a grand piano played by pianist Tinna Þorsteinsdóttir. With that, I’m thinking about reverb, and how the sonic environment I create enters into dialogue with reverberations within the Factory itself. I was excited to bring the vibrations or reverb from the piano into conversation with the building.

JD: Would you compare this to the acoustics inside a cathedral, where different spaces within it are meant to sustain sound in different ways? Or do you rather envision the Factory as becoming some kind of musical instrument itself?

SG: Yes, maybe the building becomes like an instrument; it makes sense to think of it like that. The Factory’s architecture is very interesting: it is, in a way, like a musical instrument in that it is completely symmetrical, with entirely straight lines and rectilinear forms. Then there are holes throughout the building, and light and air penetrate these openings. Light and air enter the frame, then become the visual component as they merge with the sonic environment in the wings.

JD: How are you thinking about the work in the context of the building and the architecture?

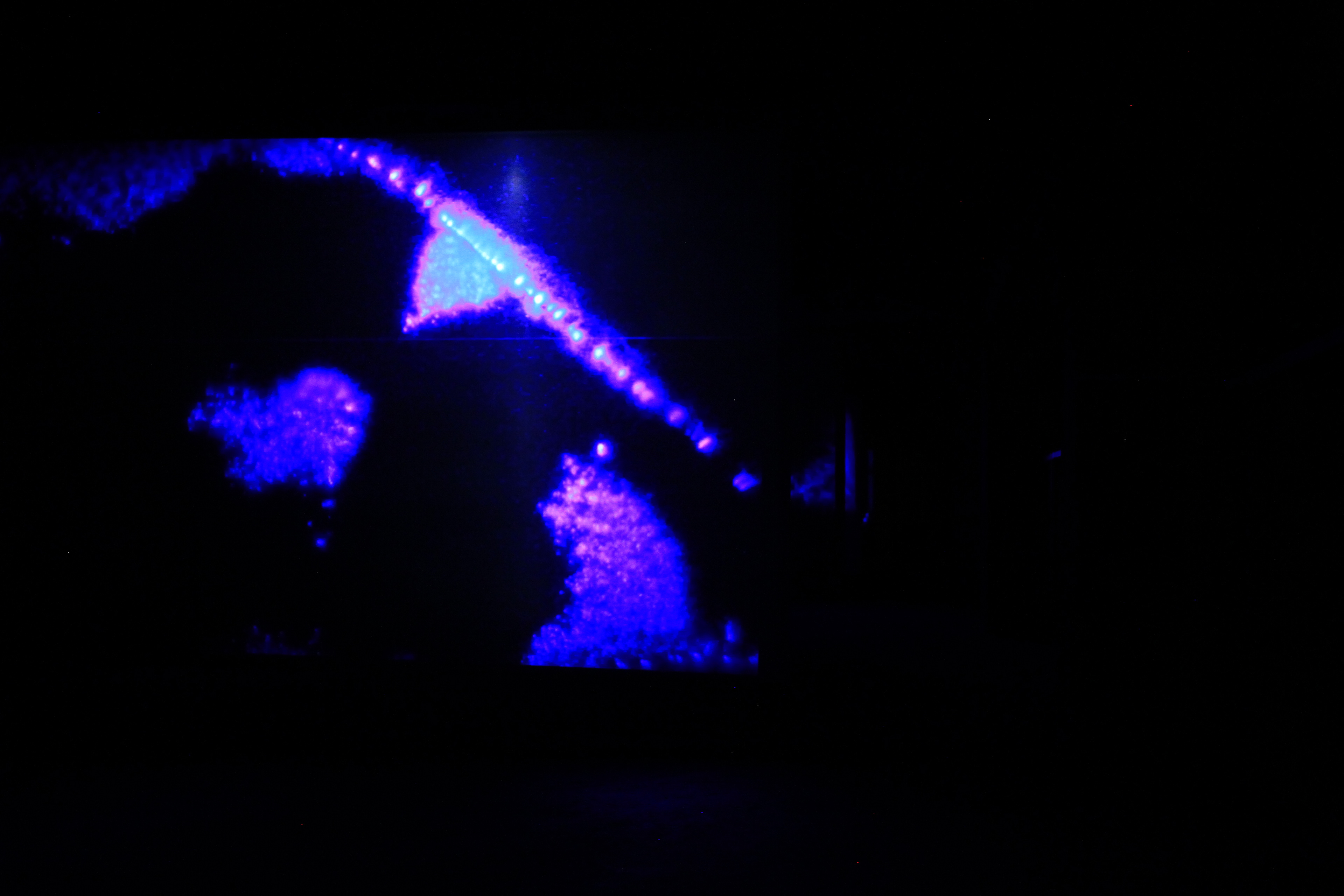

SG: I’m working with the centre of the building (three floors), and I think of the exhibition as one large moving-image sculpture intertwined with the building itself. I use 150 × 300cm aluminium sheets to arrange a path down the length of the mezzanine; the whole structure is about 5 × 40 meters. Although it’s enormous in length, there is also an intimacy you feel when walking through it, so the work could function as a mise-en-abyme. In addition, the big halls offer interesting perspectives of the work from the ground floor.

JD: Do the visual elements function organically?

SG: The visual imagery transforms from one landscape to another in a continuous flow; there is constantly one scene after another, and this movement then repeats itself every thirty minutes. The filming process is also very organic. It’s like spraying with a spray bottle: I hardly frame anything, just point the camera in different directions, and it almost becomes a visual storm.

JD: How are you thinking about the work in the context of the building and the architecture? SG: I’m working with the centre of the building (three floors), and I think of the exhibition as one large moving-image sculpture intertwined with the building itself. I use 150 × 300cm aluminium sheets to arrange a path down the length of the mezzanine; the whole structure is about 5 × 40 meters. Although it’s enormous in length, there is also an intimacy you feel when walking through it, so the work could function as a mise-en-abyme. In addition, the big halls offer interesting perspectives of the work from the ground floor.

JD: Do the visual elements function organically?

SG: The visual imagery transforms from one landscape to another in a continuous flow; there is constantly one scene after another, and this movement then repeats itself every thirty minutes. The filming process is also very organic. It’s like spraying with a spray bottle: I hardly frame anything, just point the camera in different directions, and it almost becomes a visual storm.

JD: There’s no narrative, is there? With the entire installation, or from shot to shot, it’s not about a process of dividing a whole into smaller and smaller parts...it’s more organic than that...

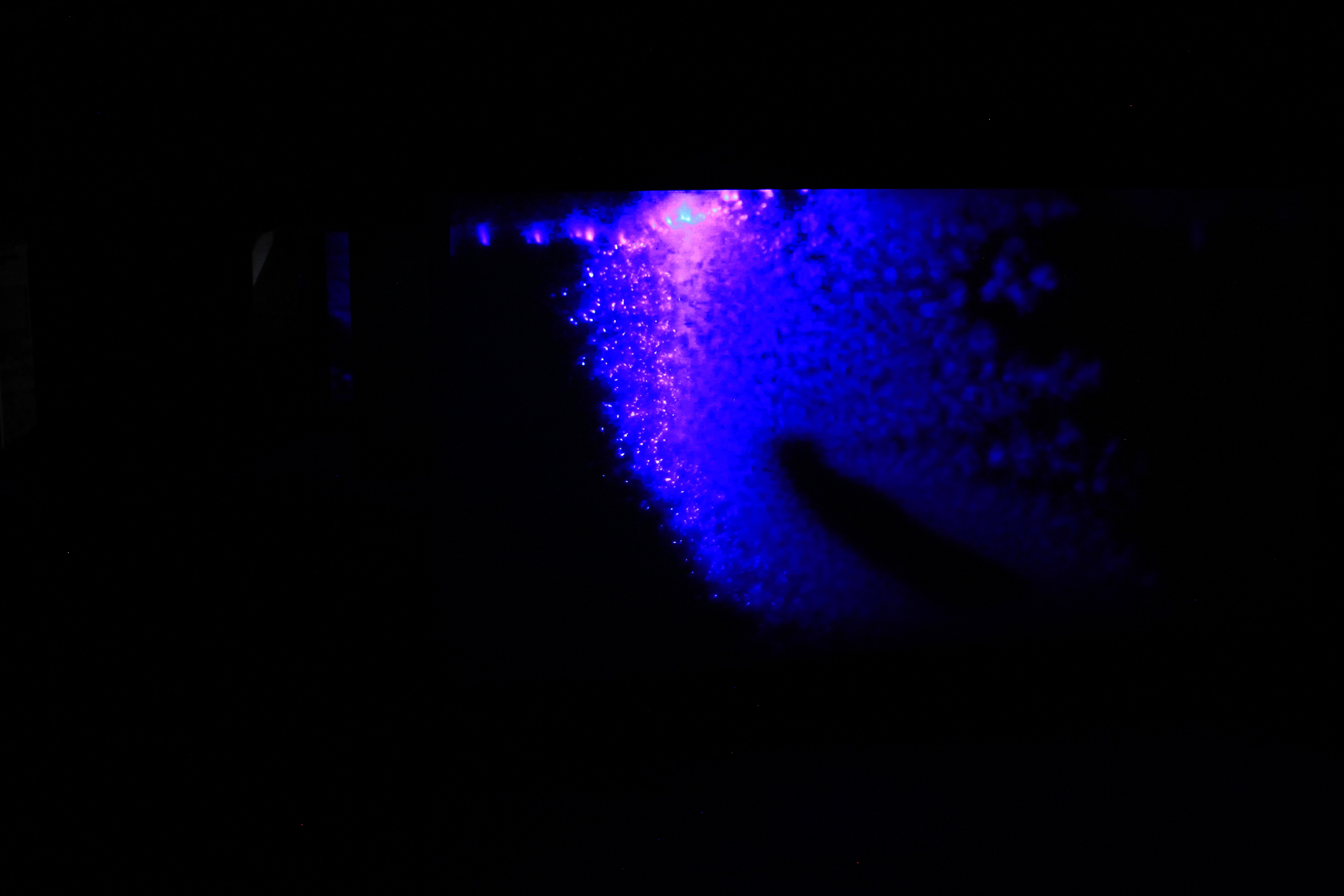

SG: Yes, I’ve made it completely randomly. I would lose a bit of control during the filming, but then I shape it through the editing, which requires a lot of meticulous compositional work. It’s almost like composing a piece of music where the flow of time is very important. It starts out with wide angles and then zooms closer, then becomes a kind of close-up of sound, light, and movement that merge together into some kind of tangible electricity.

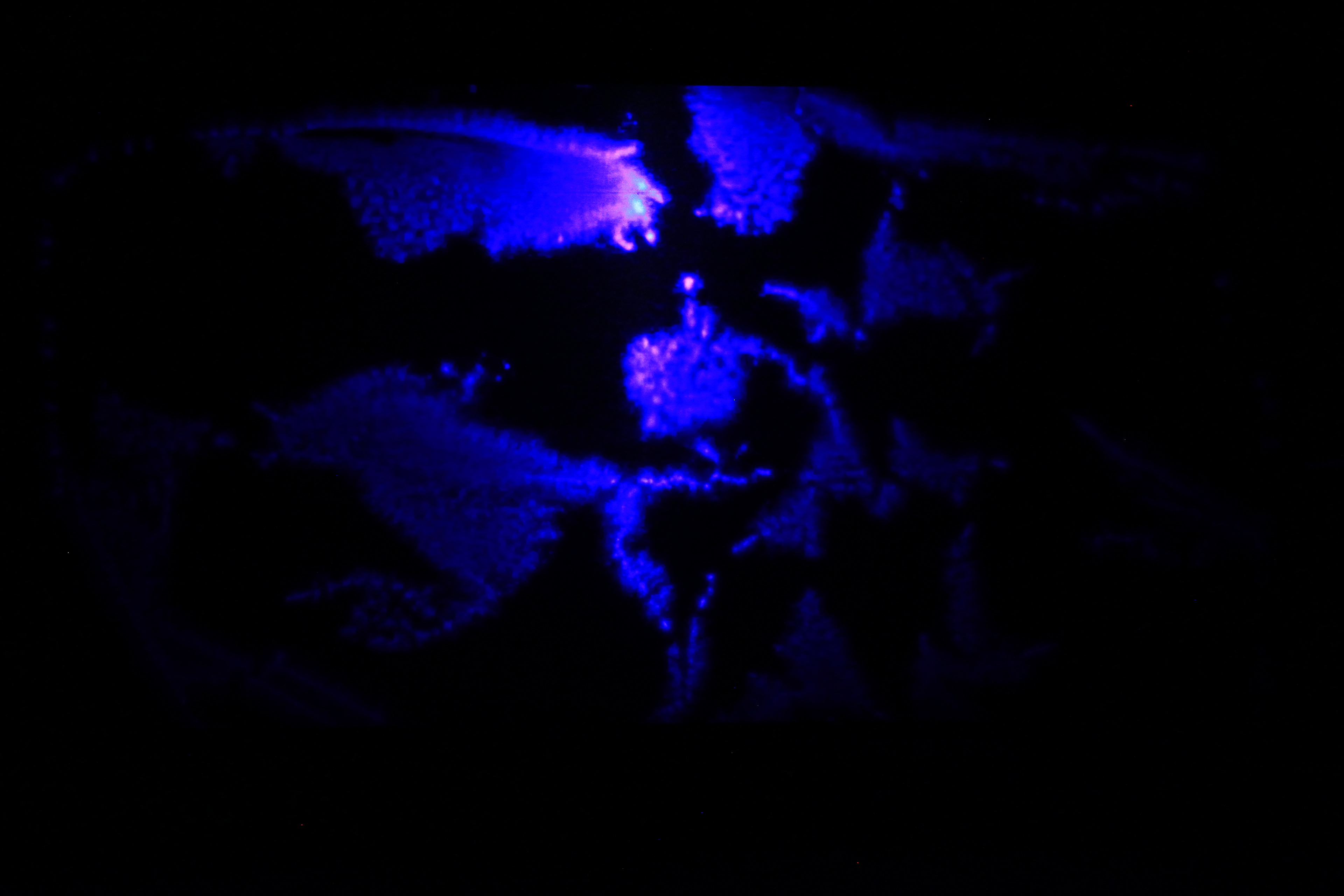

JD: And it’s quite integral in the sense that you’re always looking into this world? This whirlwind? It’s like an organism, in a way, with its cycle and its boundaries—you don’t go outside of it?

SG: Yes, you’re absolutely right. It’s like an organism. Perhaps the building as a whole is one phenomenon, and this is an organism inside it. You are always inside this world. The basis then is perhaps the colour, the movement, the light. Those are its basic elements...and energy...

JD: That’s what you’re looking at—energy—right? But there are no flashes of lightning—it’s slow and steady.

SG: At a distance, it’s slow, yes. But if you take a closer look at the details, it’s really dynamic...

JD: There are many temporalities throughout the work, both within single takes and as you move between them...

SG: Yes, there are different temporal scales, and between the screens as well—however you choose to look at the temporal aspect.

JD: Perhaps one might wonder, then, where or how time will be legible? Does the viewer interpret the passage of time as a function of movement within the work? Or, what point of reference does the viewer have to tell the time? Where do you end up?

SG: Exactly where you end up. When I’m editing this, I’m thinking a lot about the length of each segment, making sure it’s not too short—so you don’t feel each cut, or find a narrative through the editing. Each segment lasts a minute or two before it dissolves and fades into the next.

JD: Are they long enough for the viewer to stop expecting a narrative?

SG: Yes, I think it’s important for the viewer to be immersed in this world without having to think about it too much. But it’s new for me to sit down at the editing console; I haven’t done it in years. This piece involves a lot of editing, which has been a really fun process.

JD: If you just look at the storyboard on the editing console, it looks like a film.

SG: Yes, and looking at it on the console, it’s a bit like aerial views of a big city, or some sort of matrix. Flashing lights in the distance like at an airport, or occasionally like a city at night, but then it stops again.

JD: The space will be very sculptural, and your work is based on that.

SG: The aim of this exhibition and the installation was to take over the whole building—to activate and utilise the entire building, not to bring in a film that you sit on a bench and watch. Instead, each element is like a light source, or a trigger, and they ignite an experience. The Factory is a huge lump of concrete: a gloomy, black-and-white, really brutal building. It has a certain heaviness, and I wanted to create something that would contrast with that. I was always looking for this contrast, and the colour in what I’m making is very decisive. It works in opposition to the space. Maybe the building has been wishing for this, too. The space works with these works, and they also work with the building or the space.

JD: It adds a new layer of colour to this strange and brutal space. The building’s shape is odd. At the same time, it becomes less so once you understand the essence of it as a factory—that is to say, when you have some insight into the function that determined its original structure, you understand it a little better. But at first sight, it is very strange.

SG: Exactly, that is what’s so fascinating about this venue: both the geographic location and the unfamiliar world within its architecture.

JD: Maybe because narrative is absent from your work, viewers will access it through the visual rather than through a story. Are we directed straight into the visual world, into the image itself?

SG: Yes, but at the same time, we also have the sound and the building around us. Basically, I see the visual components as elements that will activate an atmosphere throughout the entire building. They’re like triggers. But the images are strong; they will be like portals.

JD: Interesting that they will be like the space, to some extent. It’s full of passages and openings.

SG: The building has a circulation system. It’s a functional building. It’s an old factory, so it had to have routes between spaces in order to work.

JD: It’s kind of amazing that the visual world you’re working with clearly has a connection to the organic—that is, to life and movement—and even though it doesn’t include anything recognisable, you can’t talk about it as abstract. You don’t go there; those aren’t the connections that come to mind. Instead, you think about time, a temporal world, rather than approaching it like a painting. Temporality comes first, which is interesting.

SG: Yes, what we are looking at is time, energy, electric light, an image generated by a highvoltage source. This is what we perceive, and it affects the viewer’s psyche. The electric light loops, forming a mechanical rhythm; at the same time, it’s organic in nature. It’s not exactly an object being observed, but rather a connection to some kind of other world.

Leiðni leiðir

Í viðamiklu rýmisverki hreyfingar og hljóðs, umbreytir Sigurður tvö þúsund fermetra rými verksmiðjunnar í fjölskynjunar skúlptúr. Jóhannes Dagsson heimspekingur ræddi við Sigurð um verkið og hvernig það leikur með tíma og orku.

JD: Verkið er væntanlega einn samfelldur hljóðheimur?

SG: Ég nálgast bygginguna sem eitt stórt hljóðumhverfi þannig að vængirnir á byggingunni eru fyrir mér sem sitt hvor rásin, hægri og vinstri, í einskonar stereo-mynd. Á milliloftinu eru holur sem hljóð ferðast á milli og eltir áhorfendur þegar þeir ganga í gegnum verkið. Á jarðhæðinni eru göng í miðju rýminu og þar má heyra upptökur af endurómi. Göngin eru fjörutíu metra löng og því tekur tíma fyrir hljóðin að berast inn í afkima byggingarinnar. Hljóðheimurinn í sýningunni er unninn í nokkrum lögum. Annars vegar er ég að vinna með rafhljóð sem koma úr myndefninu sjálfu, sem ég síðan umbreyti í vinnsluferlinu, og hins vegar er ég að vinna með upptökur af endurómi í innviði flygils sem píanóleikarinn Tinna Þorsteinsdóttir spilar á. Það má því segja að hljóðmyndin sem ég búi til eigi samræðu við hljóminn í verksmiðjunni sjálfri.

JD: Þú nálgast þetta þá líkt og hljómburð í dómkirkju, þar sem mismunandi rýmum er ætlað að bera hljóð á mismunandi hátt, eða er hægt að hugsa um þetta þannig að verksmiðjan sé þarna orðin eins konar hljóðfæri?

SG: Já, kannski að húsið sé orðið eins og hljóðfæri – það hæfir að hugsa það þannig því arkitektúrinn í Verksmiðjunni er mjög áhugaverður og hljóð bregst við ólíkum rýmum á mismunandi hátt – byggingin er að vissu leyti eins og hljóðfæri, alveg samhverf, og beinar línur og kubbar í gegnum húsið. Síðan eru göt á öllu húsinu og inn um þessi göt kemur ljós og loft.

JD: Hvernig ertu að hugsa verkið í samhengi við bygginguna og arkitektúrinn?

SG: Ég er að vinna með miðju byggingarinnar (þrjár hæðir) og hugsa um sýninguna sem einn stóran fjölskynjunar skúlptúr, sem er samofinn byggingunni sjálfri. Ég nota álplötur í stærðinni 150 x 300 cm til að búa til slóð eftir lengd millihæðarinnar; allur þessi strúktúr er um 5 × 40 m langur. Þó að það sé gríðarleg lengd, þá er líka nánd sem þú finnur fyrir þegar þú gengur í gegnum verkið, en af jarðhæðinni skapast allt önnur tenging við verkið.

JD: Myndar sjónræni þátturinn samfellda heild?

SG: Sjónræni heimurinn umbreytist úr einu landslagi í annað í samfelldu flæði; það er stöðugt eitt atriði á eftir öðru og þessi hreyfing endurtekur sig síðan á þrjátíu mínútna fresti. Tökuferlið er líka mjög lífrænt. Það mætti líkja því við að úða með úðabrúsa; ég ramma varla neitt inn, beini bara myndavélinni í mismunandi áttir og þannig verður til eins konar sjónstormur.

JD: Það er engin alltumlykjandi frásögn í uppsetningunni eða á meðal smærri hluta hennar? Það er ekki verið að brjóta upp stærri frásögn niður í minni hluta... þetta er lífrænna en svo...)

SG: Já, ég vinn það algjörlega tilviljanakennt, því maður missir smá stjórn á þessu í tökunni en svo móta ég þetta í klippingunni og sú vinna er mikil kompósisjón og nákvæmisvinna. Nánast svo móta ég þetta í klippingunni og sú vinna er mikil kompósisjón og nákvæmisvinna. Nánast eins og að móta tónverk þar sem tíminn skiptir miklu máli, fer frá víðum sjónarhornum og inn í meiri nærmyndir, svo úr verða eins konar nærmyndir af hljóði, ljósi og hreyfingu sem renna saman í eitt.

JD: Og það er alveg heilt í þeim skilningi að þú ert alltaf að horfa inn í þennan heim? Þennan klið? Þetta er eins og lífvera einhvern veginn, með þannig hringrás og afmörkun, - þú ferð ekkert út?

SG: Já, það er alveg satt. Þetta er svona lífvera. Kannski er húsið í heild sinni fyrirbæri og verkið lífvera. Maður er alltaf inni í þessum heimi. Grunnurinn er þá kannski liturinn, hreyfingin, ljósið. Það eru þessir grunnþættir í þessu… og orka.

JD: Það er það sem maður er að horfa á, er það ekki, orka? En það eru samt engar eldingar - þetta er hægt og rólegt.

SG: Já, þetta er hægt í fjarska en rosaleg keyrsla ef þú ferð inn í nærmyndina, smáatriðin...

JD: Það eru margir tímar í verkinu, þeir verða til bæði í hverri töku, og í því að færast á milli þeirra...

SG: Já, það myndast ólíkir tímakvarðar, líka á milli skjáanna, hvernig svo sem maður les tímann í þessu.

JD: Þá er kannski hægt að velta áfram fyrir sér hvar eða hvernig tíminn verður lesanlegur í verkinu? Les maður tímann út frá hreyfingu innan verksins, eða hvaða viðmið hefur maður til að lesa tímann, hvar lendir maður?

SG: Einmitt, hvar lendir maður? Þegar ég er að klippa þetta er ég mikið að hugsa um tímalengdina á hverjum kafla, að hann sé ekki of stuttur, að maður finni ekki fyrir klippi eða frásögn í klippinu. Þetta er svona ein til tvær mínútur (hver partur fyrir sig) áður en þeir leysast upp og hverfa inn í þann næsta.

JD: Þeir eru nógu langir til að maður hætti að búast við einhverri frásögn?

SG: Já, ég held að það skipti máli í þessu að maður nái að detta inn í heiminn án þess að vera truflaður of mikið. En það er nýtt fyrir mig að setjast við klippiborðið. Ég hef ekki gert það í mörg ár. Þetta er mikil klippivinna sem er svakalega skemmtilegt ferli.

JD: Ef maður horfir á klippivinnuna á klippiskjánum er þetta eins og bíómynd.

SG: Já, og ef maður horfir á þetta á klippiskjánum er þetta smá eins og loftmyndir úr stórborg eða eins konar matrix. Blikkandi ljós í fjarska eins og á flugvelli, virkar eins og næturborg einstaka sinnum sem hverfur svo aftur.

JD: Þetta verður mjög skúlptúrískt, rýmið, og verkið byggir á því.

SG: Já, það var markmiðið með þessari sýningu að verkið taki yfir allt húsið, að virkja og nýta allt húsið fremur en að koma með kvikmynd inn í húsið sem þú horfir á sitjandi á bekk. Frekar að verkin séu einskonar ljósuppsprettur eða kveikjur sem búa til upplifun. Verksmiðjan er risastór steypumassi og mjög drungaleg, svarthvít og í rauninni frekar brútal bygging. Það er ákveðin þyngd þarna og ég vildi búa til mótvægi inn í húsið. Ég var alltaf að leita eftir þessum andstæðum rýmið. Húsið er kannski að óska eftir þessu líka. Rýmið vinnur með verkunum og verkin vinna með húsinu eða rýminu.

JD: Þetta býr til nýtt litað lag inn í formið á húsinu sem er grátt og skringilegt. Það verður samt minna skrýtið þegar maður fattar verksmiðjuleiðina, það er að segja þegar maður áttar sig á þeim hlutverkum sem ráða strúktúrnum upprunalega, þá skilur maður það aðeins betur, en við fyrstu kynni er það mjög undarlegt.

SG: Já, þetta er einmitt það sem er svo heillandi við þennan sýningarstað. Bæði staðsetning hans landfræðilega og svo þessi ókennilegi heimur sem er þarna inni og arkitektúrinn sjálfur.

JD: Kannski af því að frásögninni er haldið utan fyrir þetta þá er manni vísað beint inn í myndheiminn, myndina sjálfa?

SG: Já, en svo á sama tíma erum við með allt húsið og hljóðið í kringum okkur. Í rauninni sé ég þetta eins og marga litla þætti sem koma saman og skapa ástand í allri byggingunni.

JD: Kannski áhugavert að það verður eins og rýmið að einhverji leyti. Það er holótt.

SG: Það er æðakerfi í húsinu. Þetta er gömul verksmiðja og húsið hannað út frá þörfum gamalla framleiðsluferla og það þurfti að hafa rásir á milli rýmanna til að virka.

JD: Það er svolítið magnað að myndheimurinn sem þú ert að vinna með á sér augljósa tengingu við hið lífræna þ.e. líf og hreyfingu og þrátt fyrir að hér séu ekki þekkjanlegir hlutir, er ekki hægt að tala um þetta sem óhlutbundið, maður fer ekki þangað, það eru ekki þær tengingar sem koma upp í hugann. Maður fer eiginlega frekar inn í einhvern tíma, heim þar sem er tími, fremur en að horfa á þetta eins og málverk, tíminn kemur á undan, sem er áhugavert.

SG: Já, við erum að horfa á tíma, orku, rafmyndað ljós, mynd framkallaða af háspennugjafa. Allt eru þetta þættir sem við skynjum og hefur vonandi áhrif á sálarlíf áhorfandans. Rafljósið endurtekur sig í sífellu og myndar vélrænan takt sem á sama tíma er lífrænn. Útkoman er ekki í formi hlutar heldur ef til vill nokkurs konar tenging við annars konar heim.